One aspect of paleontological research that has always fascinated me is how amazingly similar many of the events that occurred countless millions of years ago are to those found in modern ecosystems--in this case that of the countless and wide-varied interactions between predators and their prey, and even those between the predators themselves. One of these behaviors is something known as 'head biting'--a behavior observed amongst living animals in which competing rivals (over a mate, territory, a corpse, many things) fight amongst each other for control over whatever it is that they have their eyes set on. And because each of these animals are trying to assert their dominance over the other and would like to keep themselves as intact as possible, the head is a frequent target (keeping the rival in their sights). Also, because carnivores of aeons past had the same goals in mind as those living today (self-preservation and reproduction) and very similar tools to do so with (teeth and jaws!), they very likely ran into similar encounters and bouts of combat. As it turns out, we can find signs of these encounters throughout the fossil record!

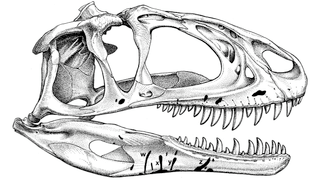

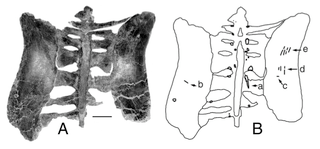

This is a drawing of the partially reconstructed skull of an animal called Sinraptor, found in the deserts of northwest China. Each of the dark black lines outline the path of bite wounds that Canadian paleontologist Phillip Currie believes were caused by a conspecific (another Sinraptor). What is unique and so absolutely cool about this find is the fact that it allowed Currie to reconstruct the event in fascinating detail (given that it occurred over a hundred million years ago!)--two carnivorous dinosaurs faced off over a number of possible things (food, territory, etc.)--the tensions breaks, and one of the pair snaps its teeth at the other on the right side of the face and lower jaw with the right side of its mouth (measured by the angle and direction of the bite marks). However, as evidenced by the fact that the injuries were partially healed we know that the dinosaur in question (somehow) fled the scene. On the other hand, not all conspecific combat avoids mortality. In fact, we have evidence of outright cannibalism by this guy--

This is a drawing of the partially reconstructed skull of an animal called Sinraptor, found in the deserts of northwest China. Each of the dark black lines outline the path of bite wounds that Canadian paleontologist Phillip Currie believes were caused by a conspecific (another Sinraptor). What is unique and so absolutely cool about this find is the fact that it allowed Currie to reconstruct the event in fascinating detail (given that it occurred over a hundred million years ago!)--two carnivorous dinosaurs faced off over a number of possible things (food, territory, etc.)--the tensions breaks, and one of the pair snaps its teeth at the other on the right side of the face and lower jaw with the right side of its mouth (measured by the angle and direction of the bite marks). However, as evidenced by the fact that the injuries were partially healed we know that the dinosaur in question (somehow) fled the scene. On the other hand, not all conspecific combat avoids mortality. In fact, we have evidence of outright cannibalism by this guy-- Majungasaurus, a large theropod dinosaur that lived in modern day Madagascar 70-65 million years ago. One find in particular viscerally fleshed out the defleshing of one such animal by another of its own species--the tooth marks on the bone match the dinosaur's teeth perfectly.

Looking at today's ecosystems, this sort of thing is none too surprising--it occurs more frequently than many realize. What is exceptional (being that fossilization alone is very rare) is the signs of its existence being preserved after so long!

Looking at today's ecosystems, this sort of thing is none too surprising--it occurs more frequently than many realize. What is exceptional (being that fossilization alone is very rare) is the signs of its existence being preserved after so long!  However, encounters were certainly not limited between the carnivorous dinosaurs themselves--we have also uncovered fantastically detailed evidence of predator/prey interactions (both of animals that were scavenged and animals that escaped attack).

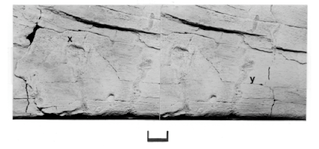

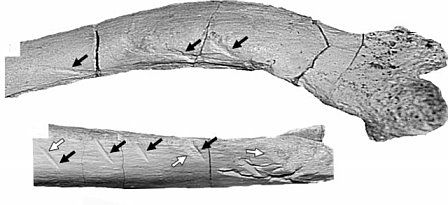

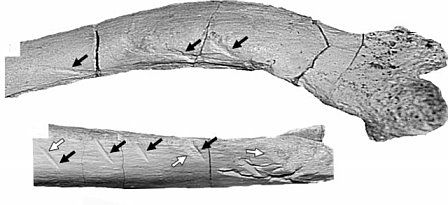

However, encounters were certainly not limited between the carnivorous dinosaurs themselves--we have also uncovered fantastically detailed evidence of predator/prey interactions (both of animals that were scavenged and animals that escaped attack).  At the centerpiece of a pseudo-debate involving the feeding behavior of the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus is a skeleton re-described by paleontologist Ken Carpenter (which was first discovered by a man called Barnum Brown in 1933)--a series of its caudal (tail) vertebrae was fractured, with at least one portion of the 'spinous process' completely broken and still several others kinked. On these spines were several tooth marks that match the exact shape and size of those belonging to Tyrannosaurus. But, because the bones show signs of healing, we know that it escaped for at least some time (and possibly died due to a bone infection) created by the bite.

At the centerpiece of a pseudo-debate involving the feeding behavior of the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus is a skeleton re-described by paleontologist Ken Carpenter (which was first discovered by a man called Barnum Brown in 1933)--a series of its caudal (tail) vertebrae was fractured, with at least one portion of the 'spinous process' completely broken and still several others kinked. On these spines were several tooth marks that match the exact shape and size of those belonging to Tyrannosaurus. But, because the bones show signs of healing, we know that it escaped for at least some time (and possibly died due to a bone infection) created by the bite.

Also like many carcasses found in the wild today, bones of various dead animals would have scattered to the four winds by both assorted predators and scavengers, and as much of the bone as possible would have been picked clean. One such find is quite indicative of just that--a Triceratops pelvis collected by the Museum of Pennsylvania with a bare minimum of twelve bite marks, and as many as 33.

Also like many carcasses found in the wild today, bones of various dead animals would have scattered to the four winds by both assorted predators and scavengers, and as much of the bone as possible would have been picked clean. One such find is quite indicative of just that--a Triceratops pelvis collected by the Museum of Pennsylvania with a bare minimum of twelve bite marks, and as many as 33.

Looking at today's ecosystems, this sort of thing is none too surprising--it occurs more frequently than many realize. What is exceptional (being that fossilization alone is very rare) is the signs of its existence being preserved after so long!

Looking at today's ecosystems, this sort of thing is none too surprising--it occurs more frequently than many realize. What is exceptional (being that fossilization alone is very rare) is the signs of its existence being preserved after so long!  However, encounters were certainly not limited between the carnivorous dinosaurs themselves--we have also uncovered fantastically detailed evidence of predator/prey interactions (both of animals that were scavenged and animals that escaped attack).

However, encounters were certainly not limited between the carnivorous dinosaurs themselves--we have also uncovered fantastically detailed evidence of predator/prey interactions (both of animals that were scavenged and animals that escaped attack).  At the centerpiece of a pseudo-debate involving the feeding behavior of the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus is a skeleton re-described by paleontologist Ken Carpenter (which was first discovered by a man called Barnum Brown in 1933)--a series of its caudal (tail) vertebrae was fractured, with at least one portion of the 'spinous process' completely broken and still several others kinked. On these spines were several tooth marks that match the exact shape and size of those belonging to Tyrannosaurus. But, because the bones show signs of healing, we know that it escaped for at least some time (and possibly died due to a bone infection) created by the bite.

At the centerpiece of a pseudo-debate involving the feeding behavior of the Late Cretaceous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus is a skeleton re-described by paleontologist Ken Carpenter (which was first discovered by a man called Barnum Brown in 1933)--a series of its caudal (tail) vertebrae was fractured, with at least one portion of the 'spinous process' completely broken and still several others kinked. On these spines were several tooth marks that match the exact shape and size of those belonging to Tyrannosaurus. But, because the bones show signs of healing, we know that it escaped for at least some time (and possibly died due to a bone infection) created by the bite.

Also like many carcasses found in the wild today, bones of various dead animals would have scattered to the four winds by both assorted predators and scavengers, and as much of the bone as possible would have been picked clean. One such find is quite indicative of just that--a Triceratops pelvis collected by the Museum of Pennsylvania with a bare minimum of twelve bite marks, and as many as 33.

Also like many carcasses found in the wild today, bones of various dead animals would have scattered to the four winds by both assorted predators and scavengers, and as much of the bone as possible would have been picked clean. One such find is quite indicative of just that--a Triceratops pelvis collected by the Museum of Pennsylvania with a bare minimum of twelve bite marks, and as many as 33.

I'm a forensic odontologist and this is a fascinating story on bitemarks. I have some experience with critter bitemarks- alligators, dogs, etc, but none quite like this. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed it!

ReplyDelete